CIVIS MEDIA DIALOGUE 2024

Too narrow, too gloomy?

The new format of the CIVIS Media Foundation explores the connection between diversity of perspectives and media trust.

Journalism is a matter of trust. Because, says CIVIS executive Director Ferdos Forudastan, “whether a diverse society functions depends very much on how journalistic media report” and whether people trust the media. For many viewers, listeners and readers, trust depends on the answer to this question: “Does my channel, my newspaper, my online medium reflect different perspectives, but definitely also my perspective?”. Media trust and a diversity of perspectives are therefore fundamental to an open society and liberal democracy. It is this context that the CIVIS executive director recalled in her welcome address to the first CIVIS Media Dialogue. And it is the basic idea behind the new format premiered in Berlin in January 2024.

The CIVIS Media Dialogue is a development of the CIVIS Media Conferences and, like these, will take place once or twice a year. Media professionals, academics, representatives of non-governmental organisations and foundations meet in smaller groups – some in public, some without cameras and microphones – to exchange views and information on current media policy issues. The co-host of the premiere is Stiftung Mercator, which has invited participants to its ProjektZentrum in Berlin.

For the first edition of the new format, the organisers have focused on a particularly topical question: Under the title “Something missing?”, the participants discuss the diversity of perspectives of public broadcasters (ÖRR) – a topic that is the subject of a heated debate in the current turbulent times. The ÖRR in particular is confronted with a great deal of suspicion. “One-sided”, “pro-government”, “unrealistic”, “elitist” – there is no shortage of critical, sometimes damning judgements.

This has an impact on the key issue of trust. It is a crumbling commodity. According to the Mainz long-term study ‘Media Trust’, 62 percent of those surveyed recently indicated that they still trust the ÖRR. To co-host Christiane von Websky, Head of Participation and Cohesion at Stiftung Mercator, it is an ambivalent finding. On the one hand, it is still a remarkably high rate, on the other it is the lowest ever recorded – “we should take this all-time low seriously.”

Professor Marcus Maurer from the Institute of Journalism Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz and his team are providing an empirical basis for part of the discussion with a new study on “Diversity of Perspectives in Public Service News Formats”, the starting point for the media dialogue. Maurer and his colleagues Pablo Jost and Simon Kruschinski have analysed almost 10,000 news programmes from April to June 2023, including productions from nine public broadcasters. For comparison, they also looked at content from private providers, both from radio and print media. The method takes into account the difficulty that the most important requirements of media legislation, “diversity of opinion” and “balance”, are not precisely defined. Comparisons are therefore easier than absolute statements.

Maurer himself presents and explains the results of the new study. In terms of the topics and people mentioned (“actors”) or quoted (“speakers”), there are “incredibly great similarities” between public and private broadcasters: Economy and labour are the leading issues, minorities hardly play a role, German political actors and parties dominate.

Common ground also prevails as far as evaluation is concerned – not in commentary form but in terms of the distribution and weighting of voices on a given subject matter. It is true that the governing parties SPD and the Greens perform slightly better on public television than on private television. But the following applies to both: there is an “extremely strong focus on negative reporting about the parties” (Maurer).

So what does this mean to the key question of “Something missing?” According to Maurer, public service broadcasting is in the mainstream in terms of diversity and balance, and no serious shortcomings can be identified. Worrying, however, is the weighting – the clearly negative bias in political reporting. This could play into the hands of populist strategies to delegitimise the political business. Maurer: “When we see that all established parties are portrayed as ultimately incompetent when it comes to solving political problems, you can obviously assume that the AfD profits from this.” In addition, conservative views are slightly less well represented than liberal-progressive ones when it comes to basic social orientations.

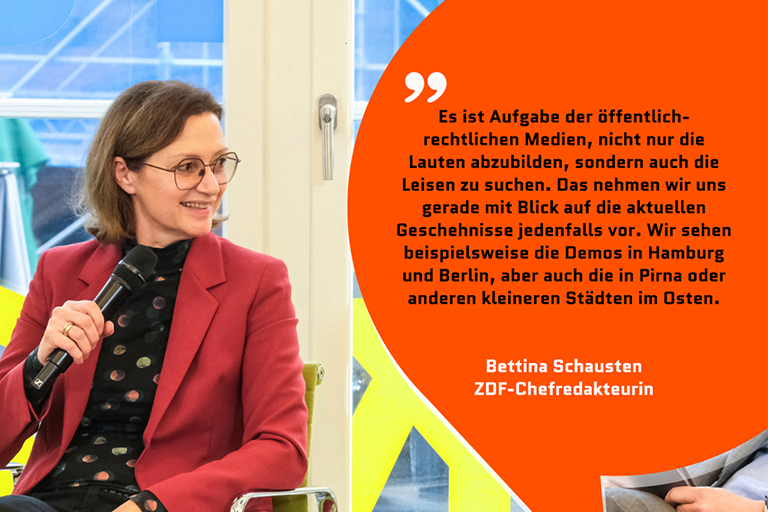

In the subsequent expert panel of the CIVIS Media Dialogue, journalistic practitioners in particular discussed the findings. ZDF Editor-in-chief Bettina Schausten believes that the study thankfully counters wide-spread prejudice: Claims that the public media are “alternately mendacious press, state broadcasting or red-green smug […] In this respect, the result of this study corrects the general picture. I find that positive.” There is also “an interesting collateral result”, she adds, “namely the question: are we all reporting too critically about the political class?”.

Stefan Brandenburg, Editor-in-Chief of WDR Aktuelles, is also satisfied that the study provides no evidence of a left-green agenda at ÖRR. “The other question, however, is: Are we good enough?” That is not the case. A critical approach should not turn into outright mercilessness. The stated predominance of a welfare state orientation over market economy ideas should also be questioned.

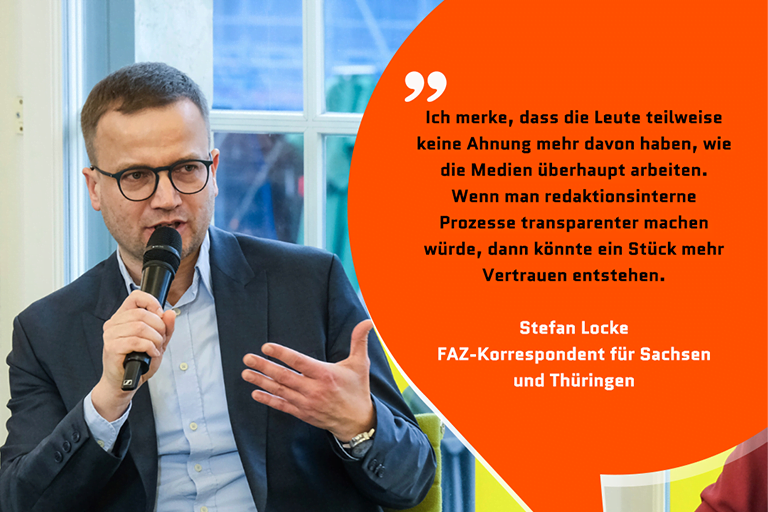

For communication and media expert Nadia Zaboura, representation is a key point. “Who is allowed to speak?” News, she argues, is too rarely about minorities or marginalised groups, who are also too seldom heard themselves. Stefan Locke, a correspondent for FAZ in Saxony and Thuringia, points to what he considers “the largest minority” of all those overlooked – the constantly ignored population of East Germany. That is “fortunately over”, Schausten interjects.

Nevertheless, the panel agrees that there is no reason for complacency. “So what could be improved?”, moderator Leonard Novy, Director of the Cologne Institute for Media and Communication Policy, wants to know. Greater diversity remains an important goal, and the results of the Mainz study have by no means made it obsolete, explains Schausten. There are more facets than covered in the study: old – young, poor – rich, urban – rural, etc. “Everyone has to pay their fees, so everyone has to figure somewhere.”

In Brandenburg’s experience, this also has to do with the fact that “we are too similar in the newsrooms […] What are the perspectives of other groups?” According to Zaboura, it should not just be about more interest in people beyond the editorial confines. Also needed are “new forms of coming together and public, trust-based, safe dialogue. Because that is exactly what is being destroyed – the fundamental trust in institutions such as public broadcasting.” Common formats, such as talk shows, need to be scrutinised in terms of who is presented there and how.

The keyword is therefore multi-perspectivity, and Brandenburg gives a practical example: the controversy surrounding the reporting on the riots and attacks at Cologne Central Station on New Year’s Eve 2015, which according to Brandenburg led to the most passionate discussion in the editorial team in recent years. On the one hand, one had to deal with the mass violence of young migrants and the women being traumatised by it, and on the other, the reality of the lives of migrants who were unjustly held jointly liable for this. However, Brandenburg says that WDR has been working for years to reform its structures with a view to increase diversity of perspectives and to create an editorial culture “in which there is more debate.”

What about the ‘negative bias’? Does the public broadcaster need to make the news more positive? There is no support in the panel for an unreflected shift towards the positive. Instead, Zaboura favours reporting that is placed somewhere between the positive and negative poles: “productive”. This does not mean being close to the state, but solution-orientated journalism. Schausten takes a similar view. Even in view of a certain “fixation on escalation” (Brandenburg), the motto cannot be to let the government and the parties get away with bad governance. Disputes are not a bad thing in general. But “we have to report much more on the facts”, says ZDF editor-in-chief Bettina Schausten and “not only represent the loud ones, but also look for the quiet ones.”

Header: lapandr, iStockphoto

Fotos: CIVIS/ Oliver Ziebe